Automated Test Generation: Chess Puzzles with Dafny

Dafny is incredibly powerful. With it, you can prove type safety properties of a programming language, you can verify runtime complexity of an algorithm, you can identify conflicting specifications, and much more. In many cases, verification provides all the correctness guarantees that you need for your project. However, if you want to integrate Dafny code with existing codebases, you may face challenges that verification alone might not solve and where runtime testing could be useful:

- Your code is actually a reference implementation for another program, and you want to test the equivalence between the two.

- You are using Dafny’s foreign function interface, which allows implementing specifications in languages other than Dafny. Dafny can not verify such external implementations, so you want to test them at runtime to still gain confidence in their correctness.

- You have written a specification for your program and are about to embark on a proof but want to have some initial assurance that your yet-to-be-verified implementation does indeed conform to this specifications.

The following sections explain how Dafny’s built-in automated test generation functionality can help in situations like these. I will use the game of chess as an example and will prompt the test generation toolkit to idenify chess board states that satisfy a given condition, such as a king being under check. The generated tests contain the board states, while the condition is defined by the Dafny program under consideration. A brute force enumeration or fuzzing might not be up to the task here, since the number of ways in which you can arrange pieces on the board is astronomically high. Dafny, however, can use the verifier to generate tests and is, therefore, much more efficient in finding solutions.

The post is structured as follows: I will first outline a subset of chess rules using Dafny. This code serves as a reference point throughout the post. I then demonstrate the basics of test generation and discuss the different coverage metrics you can target. Using this functionality, Dafny users can visualize coverage and identify dead code. Moving on to advanced features, this post offers a broader discussion of quantifiers, loops and recursion — features that require special care when attempting to generate tests. Finally, this blogpost concludes with a summary and general guidelines for how to apply this technique to your own Dafny programs. You can also find more information on automated test generation in the Dafny reference manual. If you want to try test generation on your own, I recommend using Dafny 4.4 or greater, once it is released, and before that the latest Dafny nightly release.

1. Modeling Chess in Dafny

Chess is played on an 8 by 8 board with white and black pieces. A king of either color is considered checked if it is under threat from a piece of the opposite color. The game reaches its conclusion with a checkmate when there is no feasible way to escape a check in a single move. Let’s say you’re interested in understanding the different scenarios in which a white king can be put in check by two black knights and two black pawns. If you write down the relevant chess rules in Dafny, you can employ test generation to infer all the interesting cases.

First, let us define datatypes to describe the positions of pieces on the board and to distinguish between kings, knights, and pawns. I used a subset type declaration to constrain the legal positions to the standard 8 by 8 chess board.

1

2

3

4

5

6

datatype Color = Black | White

datatype Kind = Knight(c: Color) | King(c: Color) | Pawn(c: Color)

datatype Pos = Pos(row: int, col: int)

type ChessPos = pos: Pos | // in this declaration, "|" means "such that"

&& 0 <= pos.row < 8

&& 0 <= pos.col < 8 witness Pos(0, 0) // "witness" proves that the type is nonempty

The next step is to state how one chess piece can threaten another. Knights attack and move in an L shape, pawns can attack pieces immediately to the right and to the left of the square in front of them, and a king controls any of the squares adjacent to it. I encode these rules using the

Threatens instance predicate that returns true if a piece threatens the position provided as an argument.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

datatype Piece = Piece(kind: Kind, at: ChessPos) {

predicate Threatens(pos: ChessPos) {

&& at != pos

&& match this.kind {

case Knight(c) =>

|| ( && abs(pos.col - at.col) == 2

&& abs(pos.row - at.row) == 1)

|| ( && abs(pos.col - at.col) == 1

&& abs(pos.row - at.row) == 2)

case King(c) => abs(pos.col - at.col) < 2 && abs(pos.row - at.row) < 2

case Pawn(c) =>

&& pos.row == at.row + (if c.White? then -1 else 1)

&& (pos.col == at.col + 1 || pos.col == at.col - 1)

}

}

}

function abs(n: int): nat { if n > 0 then n else -n }

The last few rules prohibit two pieces on the board from sharing the same square and ensure we are only looking at boards with exactly one white king, two black knights, and two black pawns (a board satisfying these constraints is an instance of

ValidBoard datatype). I also define what it means for a check or a checkmate to occur.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

datatype Board = Board(pieces: seq<Piece>)

predicate BoardIsValid(board: Board) { // See Section 4 for how we can simplify this

// We want boards with specific pieces on it:

&& |board.pieces| == 5

&& board.pieces[0].kind == King(White)

&& board.pieces[1].kind == Knight(Black) && board.pieces[2].kind == Knight(Black)

&& board.pieces[3].kind == Pawn(Black) && board.pieces[4].kind == Pawn(Black)

// No pair of pieces occupy the same square:

&& board.pieces[0].at != board.pieces[1].at && board.pieces[0].at != board.pieces[2].at && board.pieces[0].at != board.pieces[3].at && board.pieces[0].at != board.pieces[4].at

&& board.pieces[1].at != board.pieces[2].at && board.pieces[1].at != board.pieces[3].at && board.pieces[1].at != board.pieces[4].at

&& board.pieces[2].at != board.pieces[3].at && board.pieces[2].at != board.pieces[4].at

&& board.pieces[3].at != board.pieces[4].at

}

type ValidBoard = board: Board | BoardIsValid(board)

witness Board([Piece(King(White), Pos(0, 0)),

Piece(Knight(Black), Pos(0, 1)), Piece(Knight(Black), Pos(0, 2)),

Piece(Pawn(Black), Pos(0, 3)), Piece(Pawn(Black), Pos(0, 4))])

predicate CheckedByPlayer(board: ValidBoard, king: Piece, byPlayer: Color) {

|| CheckedByPiece(board, king, Knight(byPlayer))

|| CheckedByPiece(board, king, Pawn(byPlayer))

}

predicate CheckedByPiece(board: ValidBoard, king: Piece, byPiece: Kind) {

match byPiece {

case Knight(Black) => board.pieces[1].Threatens(king.at) || board.pieces[2].Threatens(king.at)

case Pawn(Black) => board.pieces[3].Threatens(king.at) || board.pieces[4].Threatens(king.at)

case _ => false

}

}

predicate CheckmatedByPlayer(board: ValidBoard, king: Piece, byPlayer: Color) {

&& (king.at.row == 0 || king.at.col == 7 || CheckedByPlayer(board, Piece(king.kind, Pos(king.at.row - 1, king.at.col + 1)), byPlayer))

&& ( king.at.col == 7 || CheckedByPlayer(board, Piece(king.kind, Pos(king.at.row, king.at.col + 1)), byPlayer))

&& (king.at.row == 7 || king.at.col == 7 || CheckedByPlayer(board, Piece(king.kind, Pos(king.at.row + 1, king.at.col + 1)), byPlayer))

&& (king.at.row == 0 || CheckedByPlayer(board, Piece(king.kind, Pos(king.at.row - 1, king.at.col)), byPlayer))

&& CheckedByPlayer(board, king, byPlayer)

&& (king.at.row == 7 || CheckedByPlayer(board, Piece(king.kind, Pos(king.at.row + 1, king.at.col)), byPlayer))

&& (king.at.row == 0 || king.at.col == 0 || CheckedByPlayer(board, Piece(king.kind, Pos(king.at.row - 1, king.at.col - 1)), byPlayer))

&& ( || king.at.col == 0 || CheckedByPlayer(board, Piece(king.kind, Pos(king.at.row, king.at.col - 1)), byPlayer))

&& (king.at.row == 7 || king.at.col == 0 || CheckedByPlayer(board, Piece(king.kind, Pos(king.at.row + 1, king.at.col - 1)), byPlayer))

}

Now that we have definitions for all relevant chess rules, let us generate some tests!

2. Test Generation Basics

Let us first define the method we want to test, called Describe, which prints whether or not a check or a checkmate has occurred. I annotate this method with the {:testEntry} attribute to mark it as an entry point for the generated tests. This method receives as input an arbitrary configuration of pieces on the board. In order to satisfy the chosen coverage criterion, Dafny will have to come up with such configurations of pieces when generating tests.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

// {:testEntry} tells Dafny to use this method as an entry point

method {:testEntry} Describe(board: ValidBoard) {

var whiteKing := board.pieces[0];

if CheckedByPlayer(board, whiteKing, Black) {

print "White king is in check\n";

} else {

print "White king is safe\n";

}

if CheckmatedByPlayer(board, whiteKing, Black) {

expect CheckedByPlayer(board, whiteKing, Black);

print "It is checkmate for white\n";

} else {

print "No checkmate yet\n";

}

}

Note that I also added an expect statement in the code. An expect statement is checked to be true at runtime and triggers a runtime exception if the check fails. In our case, the expect statement is trivially true (a checkmate always implies a check) and every test we generate passes it. In fact, if you were to turn this expect statement into an assertion, Dafny would prove it. Not every expect statement can be proven, however, especially in the presence of external libraries. You can read more about expect statements here.

Now that we have all the code, you can wrap it around in a module (click here to download the source code and here to download the optimized version I discuss later in this post) and run Dafny test generation like so:

dafny generate-tests Block chess.dfy

The Block keyword in the command tells Dafny to generate tests that together cover every basic block in the Boogie intermediate representation of the program - with one basic block corresponding to a statement or a non-short-circuiting subexpression in the Dafny code. Of the three coverage criteria that you can target (more on that in a bit), this one is the cheapest in terms of the time it takes to generate the tests but it also typically gives you the least amount of coverage overall.

In particular, running the command above results in the following two Dafny tests (formatted manually for this blog post). Don’t read too closely into the code just yet, we will visualize these tests soon. My point here is that Dafny produces tests written in Dafny itself and they can be translated to any of the languages the Dafny compiler supports.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

include "chess.dfy"

module Tests {

import opened Chess

method {:test} Test0() {

var board := Board([Piece(kind:=King(White) , at:=Pos(row:=6,col:=2)),

Piece(kind:=Knight(Black), at:=Pos(row:=6,col:=7)),

Piece(kind:=Knight(Black), at:=Pos(row:=5,col:=3)),

Piece(kind:=Pawn(Black) , at:=Pos(row:=3,col:=6)),

Piece(kind:=Pawn(Black) , at:=Pos(row:=5,col:=5))]);

Describe(board);

}

method {:test} Test1() {

var board := Board([Piece(kind:=King(White) , at:=Pos(row:=0,col:=7)),

Piece(kind:=Knight(Black), at:=Pos(row:=1,col:=5)),

Piece(kind:=Knight(Black), at:=Pos(row:=1,col:=4)),

Piece(kind:=Pawn(Black) , at:=Pos(row:=0,col:=5)),

Piece(kind:=Pawn(Black) , at:=Pos(row:=0,col:=6))]);

Describe(board);

}

}

Note also that Dafny annotates the two test methods with the {:test} attribute. This means that after saving the tests to a file (tests.dfy), you can then use the dafny test tests.dfy command to compile and execute them. The default compilation target is C# but you can pick a different one using the --target option - read more about the dafny-test command here.

Often, you would want to translate the tests from Dafny code to some other format that you are using throughout your project. To do that, you can serialize every test by adding a set of print statements at the end of the test entry method. For our purposes, I wrote the SerializeToSVG method (included in the sources) that converts each test to an .svg image of the corresponding chess board. You can download the relevant image assets here (originally from tabler icons). Let us look at the results in picture form (knights are the pieces that look like a horse’s head and the white king is the only piece that isn’t filled in):

The image on the right shows a checkmate and the image on the left corresponds to the absence of either a checkmate or a check. These two tests cover all the statement within the test entry method and, therefore, provide complete statement coverage of that method. Dafny is not always guaranteed to generate the minimum number of tests required for complete coverage but here it does just that. Note that there is no test for the case in which the king is checked but can escape. Dafny could have generated such a test but under the block coverage criterion it is not required to do so, provided it can achieve full coverage by other means.

To expand the set of tests Dafny generates we can instead prompt it to target path-coverage - the most expensive form of coverage Dafny supports. The relevant command is

dafny generate-tests Path chess.dfy

We now get these three tests:

The first two tests are essentially equivalent to the ones we got before. Only the third test is new - here the king is under check but it can evade easily by moving to a number of adjacent squares. Even so, three tests seems far too few for this problem. What about a checkmate in which the check is delivered by a pawn, for example?

By default, Dafny test generation only guarantees coverage of statements or paths within the method annotated with {:testEntry} attribute. This means, in our case, that test generation would not differentiate between a check delivered by a pawn and one delivered by a knight, since the distinction between the two cases is hidden inside the CheckedByPlayer function. In order to cover these additional cases that are hidden within the callees of the test entry method, you need to inline them using the {:testInline} attribute as in the code snippet below.

1

2

3

4

predicate {:testInline} CheckedByPlayer(board: ValidBoard, king: Piece, byPlayer: Color) {

|| CheckedByPiece(board, king, Knight(byPlayer))

|| CheckedByPiece(board, king, Pawn(byPlayer))

}

Adding this annotation and running test generation while targeting path coverage wins us two more tests on top of the three we already had. We now have two checkmates, one for each piece leading the attack, and two checks.

You can continue adding {:testInline} annotation on other functions in the program to increase the granularity of your tests. A note on scalability: the number of paths through the program can grow exponentially with the size of the code base. Even for the seemingly simple example in this blogpost, trying to explore all paths after adding the {:testInline} attribute to every single function will be impossible in practice as the total number of feasible paths alone is somewhere in the millions (there are 10 different ways a knight or a pawn might attack a square if you include all symmetries, and then as many as 6 squares around the king might be under attack at the same time…). Therefore, in the majority of cases, it does not make sense to target path coverage. As a rule, you should target block coverage and consider other coverage metrics only if you are certain you need more tests. Aside from block and path, you can also target inlined block coverage (the corresponding command is dafny generate-tests InlinedBlock), which covers every block in the program for every path through the call graph to that block.

3. There is Dead Code Here

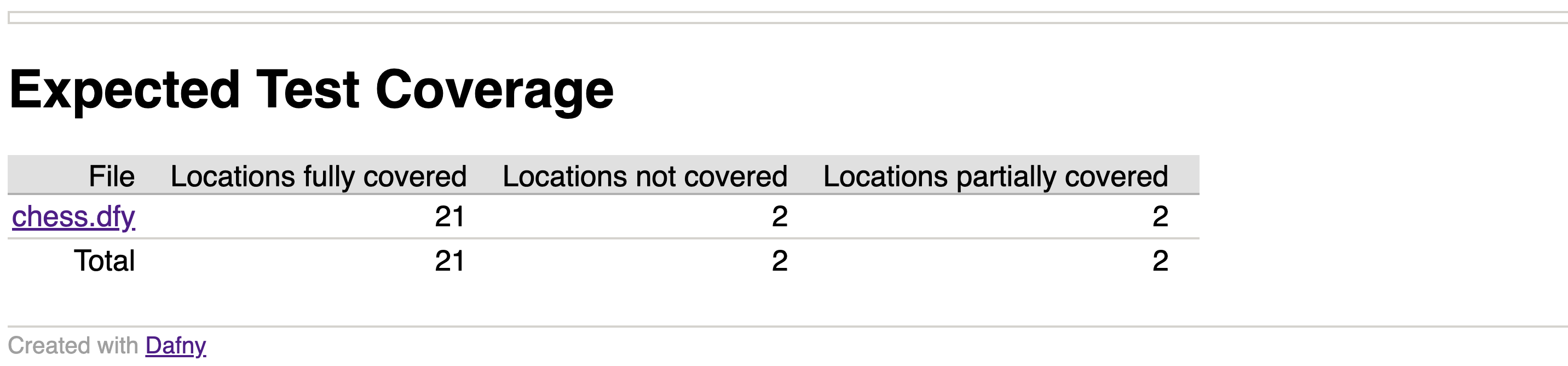

When prompting Dafny to generate tests, you can use the --coverage-report:DIRECTORY command line option to ask for a report highlighting the lines of code the generated tests are expected to cover. Such reports consist of an index file with the summary of the results and a a labeled HTML file for each Dafny file in the original program. Let us look at the report Dafny generates when we inline all of Threatens, CheckedByPlayer, and CheckedByPiece predicates. The coverage report should look the same regardless of what coverage metric you are using, so it makes sense to use the cheapest one (i.e. Block) for this exercise.

If you look at the summary file, you can see that two lines are labeled as “not covered” and two more as “partially covered”:

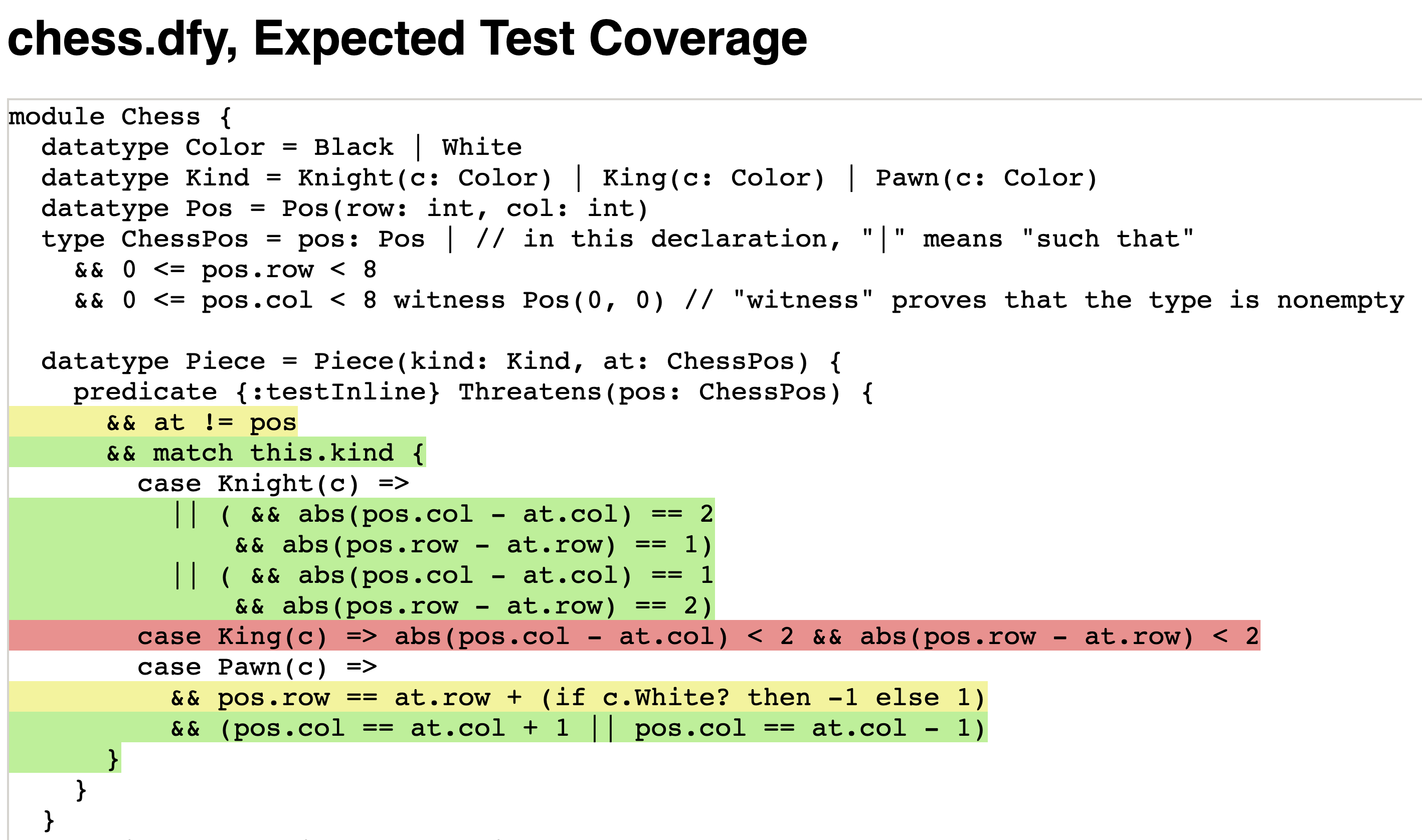

In order to understand why Dafny reports that several lines have not been covered, we can take a look at the coverage report for the chess.dfy file, particularly for the Threatens predicate:

Note that one line is highlighted in red - the line describing the rules by which a king might attack another piece. Dafny is not able to generate a test that would execute this line because this line is unreachable: we never call the Threatens predicate on a king piece. The other uncovered line in the program (not shown here to save space) is unreachable for the same reason - it is the last case in the matching expression that forms the body of the CheckedByPiece predicate.

The two lines highlighted in yellow are partially unreachable - the first one because we never check if the piece is threatening itself, the second one because there are no white pawns on the board.

Test generation can be used in this manner to detect dead code, which potentially signifies a bigger problem with the Dafny program and/or its specification.

4. Quantifiers, Loops, and Recursion

Large Dafny programs often make use of quantifiers, recursion, or loops. These constructs complicate the test generation process but it is possible to overcome the challenge they present by following three rules, which I will explain in detail in this section. The three rules are: 1) make sure all quantifiers are triggered, 2) unroll recursion up to the fixed bound during inlining and 3) avoid recursive functions in specifications and parts of the code that are not inlined.

To illustrate these rules, let us condense a part of the Dafny chess model by making use of quantifiers. As a reminder, here is the unnecessarily verbose definition of the ValidBoard predicate we have been using so far to specify what kind of chess boards we are interested in:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

datatype Board = Board(pieces: seq<Piece>)

predicate BoardIsValid(board: Board) { // See Section 4 for how we can simplify this

// We want boards with specific pieces on it:

&& |board.pieces| == 5

&& board.pieces[0].kind == King(White)

&& board.pieces[1].kind == Knight(Black) && board.pieces[2].kind == Knight(Black)

&& board.pieces[3].kind == Pawn(Black) && board.pieces[4].kind == Pawn(Black)

// No pair of pieces occupy the same square:

&& board.pieces[0].at != board.pieces[1].at && board.pieces[0].at != board.pieces[2].at && board.pieces[0].at != board.pieces[3].at && board.pieces[0].at != board.pieces[4].at

&& board.pieces[1].at != board.pieces[2].at && board.pieces[1].at != board.pieces[3].at && board.pieces[1].at != board.pieces[4].at

&& board.pieces[2].at != board.pieces[3].at && board.pieces[2].at != board.pieces[4].at

&& board.pieces[3].at != board.pieces[4].at

}

There is a lot of repetition in the code above. In order to forbid two pieces from sharing the same square, we enumerate all 15 pairs of pieces! Worse, if we wanted to change the number of pieces on the board, we would have to rewrite the BoardIsValid predicate from scratch. A much more intuitive approach would be to use a universal quantifier over all pairs of pieces:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

datatype Board = Board(pieces: seq<Piece>)

predicate BoardIsValid(board: Board) { // No two pieces on a single square

forall i: nat, j: nat ::

0 <= i < j < |board.pieces| ==>

board.pieces[i].at != board.pieces[j].at

}

type ValidBoard = board: Board | BoardIsValid(board) witness Board([])

Similarly, we can use an existential quantifier within the body of the CheckedByPiece predicate, which returns true if the king is checked by a piece of a certain kind:

1

2

3

4

5

6

predicate CheckedByPiece(board: ValidBoard, king: Piece, byPiece: Kind) {

exists i: int ::

&& 0 <= i < |board.pieces|

&& board.pieces[i].kind == byPiece

&& board.pieces[i].Threatens(king.at)

}

If we want to require our board to have a king, two knights, and two pawns, like we did before, we can now separate this constraint into a separate predicate BoardPreset and require it to be true at the entry to the Describe method:

1

2

3

4

5

6

predicate BoardPreset(board: Board) {

&& |board.pieces| == 5

&& board.pieces[0].kind == King(White)

&& board.pieces[1].kind == Knight(Black) && board.pieces[2].kind == Knight(Black)

&& board.pieces[3].kind == Pawn(Black) && board.pieces[4].kind == Pawn(Black)

}

This definition plays one crucial role that might be not immediately apparent. It explicitly enumerates all elements within the pieces sequence thereby triggering the quantifiers in BoardIsValid and CheckedByPiece predicates above. In other words, we tell Dafny that we know for a fact there are elements with indices 0, 1, etc. in this sequence and force the verifier to substitute these elements in the quantified axioms. The full theory of triggers and quantifiers is beyond the scope of this post, but if you want to combine test generation and quantifiers in your code, you must understand this point. I recommend reading this part of the Dafny reference manual and/or this FAQ that discusses the trigger selection process in Dafny.

While Dafny can compile a subset of quantified expressions, it does not currently support inlining of such expressions for test generation purposes. This presents a challenge, as it means that we cannot immediately inline the CheckedByPiece predicate above. In order to inline such functions, we have to provide them with an alternative implementation, e.g. by turning the function into a function-by-method and using a loop, like so:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

predicate CheckedByPiece(board: ValidBoard, king: Piece, byPiece: Kind) {

exists i: int ::

&& 0 <= i < |board.pieces|

&& board.pieces[i].kind == byPiece

&& board.pieces[i].Threatens(king.at)

} by method {

for i := 0 to |board.pieces|

invariant !CheckedByPiece(Board(board.pieces[..i]), king, byPiece)

{

if board.pieces[i].kind == byPiece &&

board.pieces[i].Threatens(king.at) {

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

Alternatively, we could have rewritten CheckedByPiece as a recursive function and put a {:testInline 6} annotation on it to unroll the recursion 6 times (6 is the maximum recursion depth for our example because it is one more than the number of pieces on the board). The test generation engine will then perform bounded model checking to produce system level tests. In general, reasoning about recursion and loops in bounded model checking context is known to be difficult, and so, while you have access to these “control knobs” that let you unroll the recursion in this manner (or unroll loops via the -—loop-unroll command line option), I would be cautious when combining these features with test generation. You can read the paper on the test generation toolkit to get an idea about some of the challenges. Another consideration in deciding whether or not to unroll recursion and loops is your time budget. Unrolling increases the number of paths through the program and gives you better coverage but it also increases the time it takes to generate any given test. In the end, you will likely need to experiment with these settings to figure out what works best.

With this warning out of the way, we can inline all three of CheckedByPlayer, CheckedByPiece and Threatens as described above (click here to download the source with all these changes in place). Using a loop instead of pattern matching in the body of CheckedByPiece makes the problem more scalable and we can, in fact, target path coverage during test generation. In under 10 minutes, Dafny produces 43 different tests (the number may vary with the Dafny version since I intentionally don’t unroll the loop - this reduces the number of symmetric paths but introduces a level of non-determinism). As a representative sample, the four tests below cover all the ways in which a piece can deliver a checkmate according to our definition: a pawn to the left of the king, a pawn to the right of the king, a knight that is two columns and one row away from the king, and a knight that is one column and two rows away.

Conclusions and Best Practices

If I were to summarize my own experience with developing an example for this blog post: sometimes Dafny would give you a test for a case you did not realize was possible and sometimes it does not provide a test that you would have expected it to generate. The former is a lot of fun because you uncover corner cases that you did not see right away and the latter can be a source of frustration, especially when quantifiers or recursion is involved. Yet this is also one of the main strengths of the whole approach - the guiding principles behind the tool is not any one person’s understanding of the code but the actual semantics of the Dafny program. I have learned a lot about the precise meaning of Dafny constructs by figuring out how to have Dafny generate the tests I need.

Below are five key points that I think are important to keep in mind when using test generation.

-

Read the help message: Run

dafny generate-testsand read the help message it produces - I tried my best to explain every available command-line-option and you almost certainly will need to use a few (particularly--length-limitand--verification-time-limit). The help message is always the most up-to-date description of the available functionality. -

Avoid recursion and check triggers: Dafny uses the verifier to generate tests and the verifier can sometimes put limits on the number of times it unrolls recursion, leading to incompleteness. The less recursion you have in your code, the easier it is to support test generation. If you must have recursive functions, minimize the number of recursive calls and figure out the maximum number of iterations you would need for full coverage, so as to supply this number as an argument to the

{:testInline <N>}attribute. Otherwise, you can also convert recursive functions to function-by-methods the way I do it in this post. If you use quantifiers, try to make sure they are always triggered if you are planning on generating tests (see Section 4) - otherwise the tests might not achieve complete coverage.

-

Avoid mutable types: automatically constructing mutable objects is hard, especially in the presence of object invariants, and test generation will emit a warning if you attempt to do this. Therefore, the inputs to your test entry method must be immutable (try to keep to primitive types, datatypes, sequences, sets, and subsets types). This does not mean that you cannot use class types or traits in your code, but if you do do that, you might have to write a wrapper method that takes in datatypes as input and maps them to heap-based structures.

-

Avoid non-determinism: a good test is guaranteed to hit the branch or line that it is designed to cover. If your Dafny code is non-deterministic, e.g. if you branch on a result of an

{:extern}-annotated function with no postconditions, Dafny will not be able to create separate tests that are guaranteed to cover both branches. One workaround is to constrain the space of valid test inputs and write postconditions for your external function that guarantee they behave deterministically for your subset of inputs of interest. Note that Dafny will automatically make all functions non-opaque during test generation.

An exception to this rule is the situation in which you are intentionally willing to sacrifice determinism in order to reduce the total number of paths through the program or the number of “symmetric” tests - this is the reason I don’t unroll the loop in Section 4 of this post. -

Try compiling the tests early on: you will have to execute the tests at some point and it is best to try this pipeline early on because you might have to adjust your code for test generation to work properly. In particular, if your Dafny code is not designed to be compilable, you might have to make sure that you can at least compile all input types. You might also want to implement a serialization mechanism similar to the one I created for displaying chess boards as images.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to my collaborators on the two the accompanying conference papers who all helped to make this project possible in more way that one: Aleks Chakarov, Tyler Dean, Jeffrey Foster, Eric Mercer, Zvonimir Rakamarić, Giles Reger, Neha Rungta, Robin Salkeld, Lucas Wagner, and Cassidy Waldrip.

Thank you to the Dafny and Boogie developers for their invaluable feedback on the source code, guidence on the design of the tool, and help in writing and proofreading this post: Alex Chew, Oyendrila Dobe, Anjali Joshi, Rustan Leino, Fabio Madge, Mikael Mayer, Niloofar Razavi, Laine Rumreich, Shaz Qadeer, Aaron Tomb, John Tristan, Remy Willems, and Stefan Zetzsche.

Thank you to the users of Dafny and the test generation tool in particular, who are a key motivation behind this project: Ryan Emery, Tony Knapp, Cody Roux, Horacio Mijail Anton Quiles, William Schultz, and Serdar Tasiran.